Refreshment: On the Aesthetics of Reawakening

In the ever-accelerating cadence of contemporary life, where the infinite scroll competes with the finite breath, Refreshment unfolds not as escape but as an intentional return. It is a deliberate recalibration of vision, an exhibition that invites viewers to consider clarity not as immediacy but as something slow, bodily, and ritualistic. Featuring works by Ocean, Roberta Gattel, and Mary McGee, Refreshment turns away from spectacle and instead engages the quiet and rigorous labor of seeing—of feeling time, of reclaiming attention.

Each of the three artists comes to the exhibition from distinct geographies, life paths, and conceptual frameworks. Yet they converge through a shared fidelity to repetition, mark-making, and interior resonance. Their works move across mediums—drawing, text, mixed media—and yet speak in harmonic tones. They offer practices of vision as discipline, self-reclamation, and meditative endurance.

Ocean

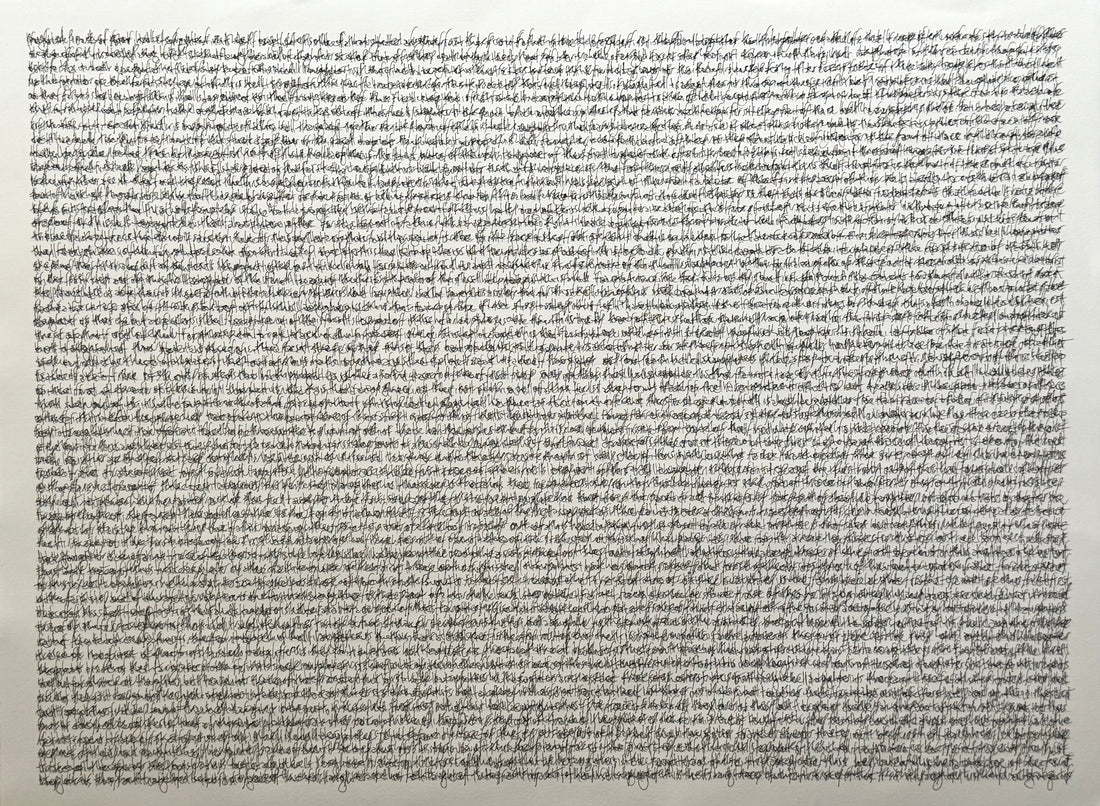

Ocean is a multidisciplinary artist and poet whose practice inhabits the space between legibility and abstraction, between word and gesture. Based in the Pacific Northwest, Ocean’s lived experience as a disabled artist informs every aspect of their work, not simply thematically but structurally. Time, for Ocean, does not move in straight lines. It loops, stutters, and pauses. Their mark-making becomes a form of temporal writing, a system of notation that resists the clarity of language in favor of the body's rhythm.

Ocean’s primary method involves writing—words, phrases, mantras—repeatedly by hand, until the letters blur into form, until meaning gives way to breath. In this way, their drawings do not ask to be read. They ask to be felt. What one encounters on the page is not a message to decode but a presence to sit with. The graphite becomes a residue of thought, and the repetition is a physical notation of endurance.

There is something both devotional and dissident in Ocean’s work. In resisting the compulsion to make their thoughts legible, Ocean reclaims illegibility as a space of power. This practice is radical for a culture obsessed with explanation, speed, and translation. It slows the viewer and insists on duration. It demands patience, and in that patience, it offers a kind of liberation—a refreshment from the tyranny of immediate comprehension.

Ocean’s work pulses at the edge of perception in the exhibition context. One cannot take it all in at once. There is no caption, no anchor—just the breath of the hand, inscribed across the surface of time.

Roberta Gattel — Drawing Breath: A Feminist Minimalism in the Shadow of Brat Summer

Roberta Gattel works between Venice, the UK, and New York, weaving quiet intensities into the language of graphite. Her drawings, composed of repeated, delicate pencil gestures, invite not spectacle but attention, offering slowness as both aesthetic and resistance. Her work is not about saying something loudly but about being present precisely and insistently, even in silence.

At first glance, Gattel’s restrained minimalism may appear distant from the cultural irreverence of Brat Summer, a 2024 phenomenon sparked by Charli XCX’s album Brat. With its acidic green aesthetic, brash persona, and refusal of “respectable femininity,” Brat Summer became a catch-all for messiness, unapologetic girlhood, and cultural disobedience. But while Gattel’s approach may be quieter, it resonates powerfully with the deeper spirit of the brat: a refusal to conform.

Gattel’s practice embodies a subtler, but no less radical, feminist defiance. She chooses repetition, subtlety, and imperfection in a world saturated with noise, perfection, and polish. Her fine lines, laid down over hours and days, do not beg to be seen—they require the viewer to slow down, to meet the work on its temporal terms. This act, in itself, is feminist: it reclaims space not through spectacle but through duration.

Her minimalist drawings meditate on care, perception, and bodily labor. Every pencil stroke is a breath, a unit of time, a moment of being. In this way, her work parallels the emotional landscape of Brat Summer: women reclaiming the right to exist outside the expectation of grace, order, or clarity. While Brat Summer externalized chaos and joy, Gattel internalizes reflection and control, but both resist the same cultural ideal of the “clean,” well-behaved woman.

Gattel’s feminism is not declarative but formal. She doesn’t use slogans or icons; she uses space, texture, and repetition to assert presence. Her art models an alternative mode of female subjectivity: one that does not shout to be heard, but remains. Her work asks: What does it mean to endure? To repeat? To draw without rushing toward a conclusion?

In the context of Refreshment, Gattel’s work counterpoints louder visual expressions of liberation. She offers another way of being free—through stillness, concentration, and resilience. Her practice reflects not just how women may act but how they might feel: steady, unresolved, present.

Amid the cultural aftershock of Brat Summer, Roberta Gattell’s quiet, contemplative drawings offer a different kind of clarity—one that arises not from rebellion alone, but from the radical commitment to remain exactly as one is, without apology.

Mary McGee

Where Ocean works through illegibility and Gattel through minimalism, Mary McGee enters the exhibition as a force of emotional clarity. A multidisciplinary artist based in New York, McGee draws from her Catholic upbringing and embodied spirituality to create works that feel at once sacred and subversive. Her practice weaves painting, drawing, text, and sculpture into assemblages that function as modern-day altars—sites of confession, remembrance, and reclamation.

McGee’s work is rich with color—deep reds, glowing golds, aching blues. Her compositions are layered: fragments of prayers, journal entries, and symbolic forms. Through these materials, she constructs visual narratives of shame and healing, repression and self-affirmation. Her work carries the weight of personal history but is never insular. Instead, it opens outward, offering its vulnerability as an invitation.

There is something fearless in McGee’s willingness to confront spiritual structures from within. Rather than rejecting the religious forms that shaped her, she reclaims them—bends them, dyes them, makes them hers. In her hands, the altar becomes not a place of judgment but of return. The icon becomes not dogma but a mirror.

In Refreshment, McGee’s work serves as the emotional heart of the exhibition. It reminds us that clarity is not always achieved through distance or detachment. Sometimes, it is found in the heat of feeling, in naming what has been hidden. McGee’s work does not ask the viewer to analyze; it asks them to feel. And in feeling, to be renewed.

Her contributions remind us that refreshment is not always gentle. Sometimes, it comes through rupture. Through the courage to reclaim the sacred on one’s terms.

Toward a Philosophy of Refreshment

The convergence of these three practices—Ocean’s rhythmic resistance, Gattel’s philosophical pause, and McGee’s ritual reclamation—forms a composite vision of what “refreshment” can mean. It is not spa-like serenity. It is not a commercial cleansing. It is not a voiding of responsibility.

Instead, Refreshment posits clarity as something hard-won. It emerges through repetition, silence, and the courage to confront the unspeakable. It is a renewal not of the senses alone but of the soul.

This is a show about time—not linear, capitalist time, but lived time—felt time—the time of breath, ritual, and marking and unmarking. It is about what it means to attend, slow, and trace. It is about reinhabiting perception.

It is also a show about labor—the labor of mark-making, the labor of healing, the labor of being present with what is difficult. Each artist works slowly and patiently. Their materials are not loud, but they echo deeply. They require the viewer to bring something of themselves—to meet the work halfway.

Finally, Refreshment is about return—return to the body, to slowness, to ritual, to self. In a world obsessed with forward motion, with escalation and productivity, this exhibition proposes something far more radical: stillness as power, clarity as confrontation, repetition as revelation.

Through these works, we do not escape the world—we return to it differently—with new eyes, steadier breath, and attention that is not drained but refreshed.

Artist statement

OCEAN

Born

And shall return into solution

Liquid amniosis

Sea

To a time that no longer remembers in its inmost skeletal wail

A mother epiduraled & Cesareaned & then

The nursing on formula & cartoons & all the playground degradations

& o god o god Time cascading toward the hospital diodes like a crown

All exits barricaded

Must i come in must i go

—To a time before all that

Remember: under civilization

We are earthborn

These words come down through the grunts of animals

Washes of grasses high on the ancient steppes

Winds mewling across plateaus

The slush of tides glinting in solar light

As though signaling to the shores they erode

& that happiness

Strewn among our birthrights

Waits foxcoy for us

To birth across our face

Its teeth

…And yet who can forget? Our “pain”:

The hole which the self loves to prove to itself that it is

Down which we throw so much attention

& demand others throw theirs

As though that most precious commodity naught

Meanwhile there’s a whole ecosystem thing doing its thing around our Narcissus thing

Beavers shore up our void dragging gnawed alder boughs

Morels & fiddleheads sprout on the outlying lip of the hurt

It fills in with spring water & newts & turtles

Mayflies careen over & redwings & cumulus

While far away over our emptiness the Aurora writhe in skeins of light

& resounding in the howls of such light & of babies & humpbacks & wolves

Can be heard joy birthing anew as the beings of this world

Try to plait the grimaces we don to carapace our terror & our longing

Into smiles to signal to our fellow primates

That each gift of love which death bestows on life by its passing

Renews us in fellowship at the shared feasting table of lifeOf this remind us

When in the midway of this having-been-born we forget:

That though we wake to concrete poured over the exits

Our laughter carves a tunnel

Roberta Gattel

Brat Summer

Introduction

I started working on the Brat Summer project, collecting many interpretations of the theme from the web, at the end of June 2024, following the aesthetic-cultural trend launched by the English pop singer Charli XCX with the release of her latest album “Brat” on June 7, 2024; and I continued to gather suggestions, comments and posts on the topic until the end of August 2024.

The music album addresses the complexity of being a woman in Contemporary Western society: it highlights vulnerability, insecurity, self-doubt but also hedonism, a proud self-expression, suggesting to embrace one’s messy being without fear (Pop Culture Dictionary, 2024). The adoption of the “Brat” as a lifestyle began shortly after the album’s release and was characterized by anti-conformist attitudes towards what is expected of a woman: the refusal to always be the clean, tidy, attentive to the pleasure of others woman that society expects (Williams, 2024) and a “don’t care” attitude, also reflected in a specific fashion style (reminiscent of Y2K and edgy elements) (Dow, 2024; Peralta, 2024). But beyond fashion, the Brat Summer Trend represented a renewed focus on the search for one’s authenticity and on the rejection of the fear of being oneself.

The acid green color, which characterizes the album’s art and branding (picture 1), became its symbol, appearing in social media, fashion and even in political campaigns (Clarke-Billings, 2024). In this article I explore not only the artistic and methodological process behind the creation of the installation “Brat Summer” but also its meaning within my artistic research, and the positioning of my work and the themes I investigate within contemporaneity.

I consider this installation important because it represents a work of collection and visual translation of political life and social expectations. Through the presentation of what brat is, the installation offers a glimpse of the contemporaneity of summer 2024: from Kamala Harris's electoral campaign to the Olympics, from the fires in Greece to the Israeli-Palestinian war, from the gender issue to the trends of the moment. The installation Brat Summer wants to show howmainstream culture, pop and fashion manage not only to reflect a historical moment but also to embody people's hopes and aspirations. But above all, it wants to dismantle the idea that popular culture, and fashion especially, are separate from political life - according to the same dualism that wants personal life to be separate from public life (Hanisch, 2006) - showing instead how fashion and politics are (and have always been) closely intertwined (Bartlett, 2019).

[1]

Approaching Brat Summer: context, background, influences

Struck both by the strong political, aesthetic and social transversality of the Brat Summer phenomenon (Ferraro, 2024; Peddie and Bandilla, 2024), and by the happy reception it had found among teenagers and young women (Millette, 2024); and intuiting how this response could be the mirror of a deeper social and gender anger (“from the rolling back of reproductive rights to the withering of the #MeToo movement”) (Hancock, 2024), I asked myself how I could analyse the phenomenon and make its potential manifest on a level that would not diminish what for me was its novelty and transformative power. Since fashion trends are associated with nihilism and the mutability of the period, that is, with the cycle of rapid obsolescence where what is current is immediately surpassed by something else, reflecting the tendency to reduce to nothing what has just been (Galimberti, 2022; Olivier, 2006; Maldonado, 2001); since, despite the spread of social media culture (Bolter, 2019), the gap between elite culture and mass culture has not yet been fully recovered today, leaving the latter on a plane of inferiority and lower relevance - when not in a plane of complete invisibility (Wurth, 2019; Gans, 2009; Crane 1992), I decided to resort to artistic space in terms of a space of fundamental expressive freedom where dignity of social discourses can be restored (Djajić and Lazić, 2021) and where a popular art that not only expresses politicalideas but also represents a space of collective interaction can be valorized (Widrich, 2023).

I therefore resorted to drawing and installation to create a place where I could visually and critically address the issues raised by the Brat Summer phenomenon, removing it from a lens that wants it to be just a nihilistic machine and an expression of low culture, and giving back to it the strength of Its voice as I heard – and felt - it.

I started researching the Brat Summer’s theme on the web from social networks, articles, posts, images and memes, thus noticing how the Brat Summer lifestyle had quickly moved from a geographically specific gender dimension (for example, in England, the refusal of the bra) to an international political activistic dimension (the presidential elections in America). Collecting what was said about Brat Summer on the web was like building a puzzle day by day without clearly knowing what the subject represented was nor how big the picture was. It has been an unpredictable, challenging and incredibly interesting experience.

I started translating the words and comments I found into images (picture 2), copying existing memes and images (pictures 3 and 4), re-interpreting them (picture 5) and illustrating the lyrics of the songs (pictures 6 and 7), finding myself, at the end of the summer, in front of a hundred fragments that ranged from funny nonsense to political denunciation. And it was like finding myself in front of a piece of collective diary written by many invisible hands through mine.

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

My personal experience as a woman from a working-class background, my professional career as a teacher working in socially disadvantaged contexts, my humanistic academic background and my vital passion for gender issues have profoundly influenced me in the conception and development of this work. These elements of my experience and training led me to remain tied to realistic figuration, so that the work could be “readable” directly by anyone; guiding my focus on the socio-political side of the phenomenon, and therefore on the hybrid nature of media interaction that involves civic involvement, frivolity and different levels of engagement; trying not to neglect the

poetic side of the work, which wants to be usable and socially engaged, but also to present itself in an elegant way, translating the digital onto paper - the format of books. And, finally, my attention to gender studies led me to pay great attention to the brat-symbols linked to what means being a woman for young women in contemporary Western society (pictures 8 and 9).

[8]

[9]

My artistic influences are heterogeneous, and range from the artistic, literary, philosophical, musical, cinematographic fields to that of social and political activism. Here I want to report only some of the figures who have been enlightening for me and who have deeply influenced my workin this last year: two artists and one writer who inspired me on a human and professional level, who reminded me how to reclaim both feminine and literary tools in art, and who held my hand as I walked through the potential and contradictions of social allyships.

I found inspiration in the authentic and overwhelming personality of the English artist Tracey Emin. In the BBC 100 Women interview, she talks about the difficulty of emerging in the white male upper middle class world of contemporary art for a working class woman with migrant background; she talks about her personal battles behind the curtain of success, her resilience, the desired accessibility of her work for a large and non-elite audience and the creation of an artistic space to help young working class artists to emerge (BBC News, 2024); she gives both an incredibly human image of herself, full of light and shadow, and a message of enormous hope. In particular, one of her sentences found a strong resonance in me: “when people say no to you, you don’t listen to them” (BBC News, 2024: 7’26’’), remembering all the no’s that I too have received and that unfortunately I have often indulged.

Now I can say that maintaining the medium of realistic drawing on paper, in the contemporary art environment, is a bit like not listening to those no’s anymore.

I recently re-discovered and re-evaluated also the work of Maria Lai, an Italian artist who achieved fame in the 80s and 90s through her works in thread and fabric (among all, the moving "Legarsi alla montagna", 1981). Even if Maria Lai never declared herself a feminist, her whole work is the result of a profound reflection on women's identity, on the symbolic value of threading and weaving as tools for relationships and for the construction of meanings (Lonardelli, 2020). She combines her love for poetry and language by embroidering the verses of her poems on the fabric pages of books. To tell her story Maria Lai uses the historically considered women's tool, the needle and thread, like a pen, men's tool. It is the testimony of an internal landscape that sees the creative act as a way to tie the people around her to her story, with the same thread she uses to write it. It transforms the action of sewing into an artistic gesture, removing it from the universe of the useful and delivering it to that of contemplation. And she does it with a proud and poetic sense of reappropriating.Maria Lai’s work reminded me that it is not necessary to separate art from literature or from other kind of subjects, but rather that through art it is possible to unite and reassemble different languages; in my case: the paper one and the digital one, the private sphere of living one's being a woman and its strongly political connotation, the summer trend of the moment and its historical significance.

Finally, the thought and the words of Emma Dabiri, Irish writer and broadcaster, helped me reflect on the potential and contradictions of social allyships within the social media. In her book “What White People Can Do Next” (2021), she highlights the limits and dangers of identity politics in contemporary times, creating a parallel with the allyships of the past and showing how the space dedicated to solidarity was once predominant compared to today; and how today the alliance is used to create opposition rather than to consolidate unions aimed at achieving a common good.

Dabiri writes:

“Yet, despite its benefits in terms of potentially democratizing opportunity, the ways social media frames information, and gamifies division, means that it is the quintessential poisoned chalice. The very nature of social media, particularly platforms like Twitter, reward outrage. […] When “activism” is bound up in a capital relations, and your Twitter persona is your brand, where is the incentive for the recognition of affinity, of solidarity across once artificially imposed lines? Technology, which promised to liberate us, and which has undeniably contributed to gains for individual women, ethnic minorities and LGBTQ+ people, is a beast of paradox. […] Together, the heavily enforced boundaries of those groups contract, cleaning out the competition, and setting up everybody outside their increasingly narrow definitions as an adversary.” (2021: 144-145)

Dealing with the Brat Summer theme as a media phenomenon characterised by a particular identity (it’s born as a feminine trend) was useful for me to reflect on what identity politics means; and to analyse and position the Brat lifestyle through this frame. From this comparison I noticed that the Brat Summer trend, despite being a social media phenomenon and despite presenting elements of identity (in fashion accessories as in the don’t care attitude), remains a vague identity trend (as Charli XCX wanted since the album's release) and therefore open to interpretation:everyone could inscribe whatever they wanted in it.

And this, unlike the social media activism that Dabiri describes, does not create boundaries but, on the contrary, it opens up to possibility.

Methodology

Since content on social media tends to be short and fragmented and since information on the web travels at a dizzying speed, passing in a few moments from one user to another, from one platform to another through a click, generating viral phenomena that often disappear with the same speed with which they manifest themselves, I chose to draw on a paper format that represents this promiscuity and this immediacy: the A5 extra thin notepad. That is, I used a type of paper not suitable for drawing but for quick pen notes, wanting to suggest how the drawn images were based on visions, emotions, volatile suggestions and referring to their impressionistic nature as notes. For this reason, even the graphic style of the drawings, while remaining realistic, is approximate and essential, with rough and imprecise lines, sometimes completely evanescent, reminiscing the spirit of quick notes.

To create a strong visual impact and suggest an immediate reference to the Brat trend, I adopted the symbolic color of Brat Summer, the acid green, using it as a base for each drawing. To avoid the visual flattening that the same type of green would have caused on each of the hundred drawings, I chose to slightly vary the tone of the color, adding more or less yellow and more or less white, in order to give a sense of movement both in the background of the single drawing (picture 10) and in the overall vision of the hundred drawings (picture 11). The sense of movement is then also reinforced by the different type of brush stroke that constitutes the green background and that, far from providing a flat background, plays on drawing different shapes, lines and scribbles, suggesting the irreverent and messy spirit of the Brat lifestyle. The choice of the acrylic paint is instead motivated by aesthetic and stylistic reasons: constituting the basis of the drawing, the pencil that writes on it is invigorated by the acrylic matrix, which expands its scratching power, while leaving the parts that write outside the green weak and diaphanous, emphasizing the evanescent effect.[10] [11]

Cited Works Bartlett, D. (2019). Fashion and Politics. New Haven and London: Yale University Print.

BBC News (2024). “In conversation: Tracey Amin”, 100 Women. Available at:https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m00271d5

Bolter, J. D. (2019). The Digital Plenitude: The Decline of Elite Culture And The Rise of New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Clarke-Billings, L. (2024). “What is Kamala Harris's 'Brat' Rebrand All About?”, BBC News, 22nd July. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cqqlgq7k374o (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Crane, D. (1992). “The High Culture Versus Popular Culture Revisited: A Reconceptualization of Recorded Cultures”, in Lamont, M. and Fournier, M. (1992) Cultivating Differences: Symbolic Boundaries and The Making of Inequality. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Dabiri, E. (2021). What White People Can Do Next. London: Penguin.

Djajić, S. and Lazić, D. (2021). “Artistic Expression: Freedom or Curse?”, The Age of Human Rights, 17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17561/tahrj.v17.6269.

Dow, M. (2024). “A Brat Girl Summer Guide For Dummies: What It Is And How To Pull Off The Trend, Betches, 10th July. Available at: https://betches.com/what-is-brat-summer-charli-lifestyle-trend-explained/ (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Ferraro, S. (2024). “Op-ed: The sociopolitical Influence of Brat Summer”, The Oracle, 7th September. Available at: http://archeroracle.org/119452/opinion/op-ed-the-sociopolitical-influence-of-brat-summer/ (Accessed: 01 July 2025)

Gans, H. J. (2009). American Popular Culture and High Culture in a Changing Class Structure. Cambridge: University Press.

Hancock, L. (2024). “The Rise Of The Female Troll: Why Brat Summer Is Really About Rage”, Elle, 20th August. Available at: https://www.elle.com/uk/life-and-culture/culture/a61912774/brat-summer-troll-culture/ (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Hanisch, C. (2006). “The Personal Is Political”, University of Victoria Online Archive, pp. 1-5. Available at:https://webhome.cs.uvic.ca/~mserra/AttachedFiles/PersonalPolitical.pdf (Accessed:01 July 2025).

Lonardelli, L. (20209. “Maria Lai: disperdersi nell’opera”, Vesper, 2, pp. 100-113.

Maldonado, F. (2001). “Pop Nihilism”, Lehigh Preserve, 9, pp. 57-65.

Millette, R. (2024). “It’s a Brat Summer and It’s Okay To Be 30”, A goof Old Fun Time (With Renèe), 2nd July. Available at: https://reneemillette.substack.com/p/its-a-brat-summer-and-its-okay-to (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Olivier, M. R. (2006). Manifestation of Nihilism in Selected Contemporary Media, MA thesis, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

Peddie, J. and Bandilla, M. (2024). “Is UK Politics Having a Brat Summer?”, PLMR, 29th July. Available at: https://plmr.co.uk/2024/07/is-uk-politics-having-a-bratsummer/#:~:text=Awkward%20attempts%20from%20politicians%20to%20manufacture%20a,the%20youth%20as%20fundamentally%20out%20of%20touch (Accessed: 01 July 2025)

Perlalta, M. (2024). “What Is Brat Aesthetic and Why Is It Trending? Experts Explain the Anti-Fashion Style”, TeenVogue, 26yh July. Available at: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/charli-xcx-brat-aesthetic-explained-by-experts (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Pop Culture Dictionary (2024). “Brat”, Dictionary.com, 8th August. Available at:https://www.dictionary.com/e/pop-culture/brat/ (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Widrich, M. (2023). Monumental Cares: Sites of History and Contemporary Art. Manchester:Manchester University Press.

Williams, Z. (2024). “Brat Summer: Is The Long Era of Clean Living Finally Over?”, The Guardian, 16th July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/article/2024/jul/16/brat-summer-is-the-long-era-of-clean-living-finally-over (Accessed: 01 July 2025).

Wurth, K. B. (2019). “Between Elite and Mass Culture”, in Rigney, A. and Wurth, K. B. (2019) The Life of Texts: An Introduction to Literary Studies, pp. 273-298. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048551903-010

Mary McGee

We often speak of “refreshment” as if it were a surface act, like closing a window and opening it again, like wiping the screen clean. But for me, refreshment is not about erasure or escape. It is about reawakening: the slow, sometimes painful return to what we’ve buried to survive.

My work begins with the body, with feelings—especially those inarticulate, unresolved, or quietly suppressed. Drawing becomes a space where the unconscious breathes; memory doesn’t arrive in complete form, but in fragments, shadows, and stains. The figures that emerge in my work are rarely whole. They are blurred, fractured, or fading—like emotional truths we almost remember, but can’t quite name.

I do not draw to represent emotion. I draw to recover it—to let it move again, without narrative, without explanation. In a culture that prizes efficiency, clarity, and composure, I offer a different rhythm: softness, slowness, and emotional depth. My lines are not answers; they are traces of a question the body is still learning to ask.

What does it mean to be refreshed, not emptied, but returned?

To feel, not as performance, but as presence?

To allow the psyche its logic, its textures, its own time?

In this exhibition, refreshment is not decorative. It is not an indulgent pause. It is a return to sensation as knowing, to feeling as a form of truth, to the self as an ongoing excavation.

Art, for me, is not a window to look through.

It is a mirror that fogs and clears—

a surface where we begin, again, to breathe.